“Graduate or advanced education is then prone to develop at the margin, as an add-on of a few more years of unstructured work for a few students. A balance has to be sought in which a graduate emphasis on research activity and research training can prosper in addition to the first-degree commitments. … There are no shortcuts in massive planning and bureaucratic organization which can bypass the need to have thousands of individually composed small worlds in which, as Humboldt stressed, the professor and the student join hands in the pursuit of knowledge.”

(Clark, 1993, 356, 378)

Research has been a buzz word since the end of the Second World War (1st September 1939 – 2nd September 1945) and become even more important and relevant at the turn of the 21st century. Research is discoursed in many policy domains, especially the higher education and industrial sectors, in relation to other trendy words such as science, innovation, development, data, technology, and the like.

Despite hardening trust and faith in the so-called “scientific research”, little is understood about the root and changing nature of (scientific) research work and research training in higher education globally. Higher education policy makers and practitioners sometimes talk about a certain research training model as if it is used the same everywhere. Such universal research training model does not exist. Countries have varying systems of advanced education and so of research training. The purpose of writing this blog is to inquire into the historical-philosophical foundations shaping the genesis and development of research training and research work at advanced education level in selected developed nations that have founded top-ranking research universities.

One way to quickly understand such foundations is to review books by leading scholars/researchers studying this area. Burton R. Clark, a well-cited American higher education sociologist, is one such scholar, and his 1993 edited book titled “The Research Foundations of Graduate Education: Germany, Britain, France, United States and Japan” can well enlighten us on how research conduct, research training, and the relationship between research and the most advanced level of higher education1 have taken shape and grown in the developed world. The book seeks to comparatively understand which countries’ advanced education have groomed the nexus among research, teaching, and higher learning (or advanced study) and whether such connection has remained intrinsically interwoven as the fundamental force of educational life in those countries. Through a comprehensive account and related macro- and micro-level evidence (from system perspective and institutional bases), the book shows us where in the world such important nexus (among research, teaching, and learning) remains functional in research training practices, how it has developed and transformed in such higher education context, and what explains its continued existence and relevance. The edited volume comprehensively addresses these and similar questions of five leading economies of the world (as suggested in its title). The five leading economies provide perhaps the best insights for histories and organizational structures of research conduct and research training at higher education institutions, partly because the university model of these countries has been adopted or adapted in other corners of the world, either through colonization or knowledge transfer.2

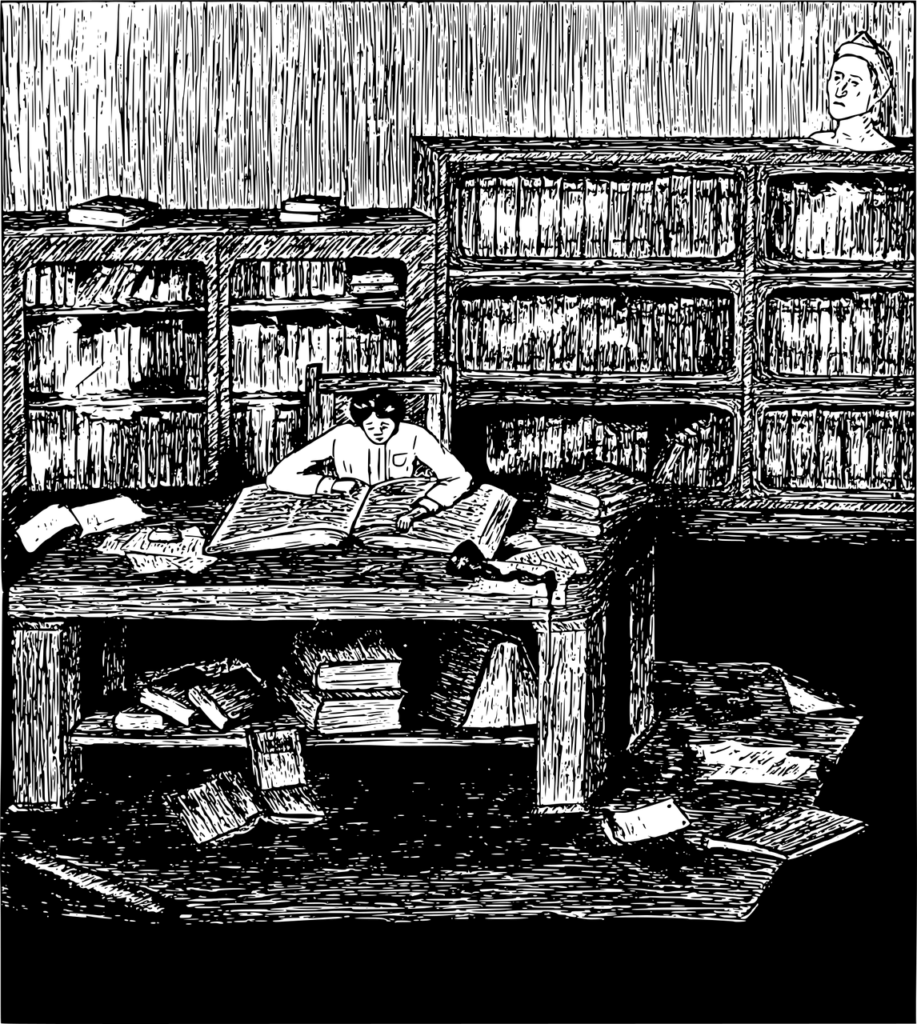

In Germany, the research conduct and research training model in advanced education basically embrace the philosophy and practice of research, teaching, and academic learning nexus since the beginning of 19th century. Shaped by Idealism, German thinkers and philosophers at that time believed that university is a place to discover truthful knowledge through Wissenschaft (academic learning and research). Wissenschaft is viewed as a “moral and practical duty” to organize observable realities in accordance with idealized “absolute knowledge”. Professors and students in the academic community are therefore considered “free thinkers” whose educational and training activities are guided by the “purpose-free process of searching for truth”. For German thinkers at that time, the knowledge- and truth-seeking approach of the university makes it a form of general education and cannot be equated with vocational education which seeks to build “skills for practical applications”. University students, according to this perspective, are not simply studiers but researchers themselves. Professors are not mere teachers but directors and supporters of students’ research projects. Both seek to master and advance their focused (and freely chosen) subject or discipline.

By the end of the 19th century, however, the ideal of the German freedom-guided and research-based university was criticized as it became less free/humanistic in how students pursue disciplinary knowledge, is oriented more towards military and industrial research, and provides too much authoritative power to the professors (the majority of whom at that time formed closer connections with politicians and industrialists). After World War II, the challenges to the German research-based approaches in university becomes even more obvious due to (1) the increase in number of students, creating a heavy teaching workload for professors, (2) the structural issues of unclear separation between the undergraduate and graduate studies and between professional and academic degrees, and (3) a relatively lower funding scheme for research from the Federal government, which leads to the move of research out of the university system to newly established non-profit research organizations (such as the Max Planck Institute).

Despite such challenges, in principle, the idealistic Humboldtian notion of university’s freedom-based research learning has remained accepted as the signature tenet to guide the organization of German universities, with a number of key ideas — such as unity of research and teaching, freedom of teaching and learning, and discovery of objective truths — deemed necessary for enlightening and democratizing the German society. But that is more in principle or theory, than in truth. In reality, according to this book, “the Humboldtian principle has been superseded by a development towards a functional segregation”, particularly between undergraduate and graduate teaching and other disciplinary and organizational structures.

In Great Britain, historically, the advanced education sub-sector also shows the link between research and teaching to some extent, basically within the doctoral education space. Undergraduate education receives a greater number of students but not very much oriented towards research. Doctoral students are better prepared to become researchers. Despite the fact that there is a research component in the master’s program (say, a 1-year full-time M.A.’s degree), such programs do not create high-quality researchers because research works during the master’s degree period are only in the form of “short dissertation” exposed at the ending phase of such program. Doctoral students, on the other hand, can work on research for a longer period of time and closely with their supervisor(s) on their research project, along with other research-related sessions such as seminars and workshops. Such “close personal supervision” and learning to do research under informed guidance are key characteristics of research training of British doctoral education.

Since the end of World War II, the British model of research training and research conduct at universities has been that of a craft or apprenticeship model, signified by the personal tutor style of training and a very specialized approach to educational designs (in terms of degree programs, curriculum, institutional focus, and number of students — especially, in the postgraduate level). Undergraduate and postgraduate education are clearly distinguished. Systematically taught courses are generally available for all levels of higher education.

There are two further interesting points to note about the way British professors conduct research and train researchers at postgraduate education level. First, they conduct research and pursue scholarship, but, unlike the German professors, it is not necessary for them to teach based on their research findings. Second, they provide close guidance to their research supervisees (generally in small numbers), leaving them [the supervisees] being trained through framed guidance than through free inquiries, as in the German context. Such practices of research training are closely related to the British approach of specialization in higher educational designs and developments, mentioned earlier, and perhaps shaped in overall by the British analytic philosophy, rooted in reductionism and atomism.

In more recent histories, postgraduate education (or graduate studies) in the British higher education contexts have been influenced more by the government’s policies and so-called research councils differentiated by disciplines — such as the Medical Research Council, the Science and Engineering Research Council, the Agricultural and Food Research Council, and the Social Science Research Council. One of the key policy discourses is whether the objective of graduate studies is to train researchers or to produce research and whether research funds should go to fundamental research or research and development in industrial settings. According to the book, the British government finally chooses so-called “strategic research” which accepts fundamental research only if it stays “within the setting of economic application and relevance”. At the time of writing the chapter, the author speculates that such narrow and selective policy choice (especially, on research funding for graduate studies) will only deteriorate the already weak unity of research and teaching at British higher education in overall.

As for the United States, research, teaching, and learning are well blended in its advanced education — particularly, in the Graduate Schools. It is generally acknowledged that the idea of the US’s higher education or its university is influenced by the German model as well as the British model. Because of such roots, the more recent term used to refer to the overarching framework of German, British, and American higher education is the Anglo-American model, deriving from the previously called Anglo-Saxon model. But because the US’s higher education system was developed in a context of mass enrolment and a diverse body of students, the organizational structure and approach to research conduct and training in graduate education are somehow different from those of Germany and Great Britain. Even many were sent to Germany to pursue science in the mid-19th century, most American scientists and scholars came back to the US, not accepting that science should be for its own sake (as somehow implied by the German Humboldtian ideal), but a collective enterprise.

In the US’s higher education systems, there is also a clear distinction between undergraduate and graduate schools and even between academic graduate schools and professional graduate schools. Academic graduate schools at universities are the main space for research conducts and research training. They provide a strong foundation for research training and research conducts and so become the base for the production of future quality researchers and academics. But it should be made clear that research in the US is also performed by other types of institutions such as government laboratories, industrial laboratories, and non-profit research institutes.

Research and science become more and more important in the US since the end of World War II due to lessons learned from the use of research-based findings for military and economic success, rise in research budget, plurality of research funding sources, and the promotion of system of peer review. Other core characteristics mentioned above (such as mass system, clear distinctions between lower and advanced levels or between academic and professional domains, competition-driven innovative initiatives of individual universities, strong connection with the Federal government and private foundations, etc.) also contribute to the significant values given to research by the US government and society. Such characteristics also allow the US’s graduate programs to integrate well among organized instructional courses, productive research engagement, and research support initiatives and therefore to maintain the strong base for teaching-learning-research nexus. All of these together generate what can be considered as the combined philosophy of pragmatism and exceptionalism of the US’s research conduct and research training at graduate education level.

There is a caution here, however. We may not try to generalize the characteristics or approaches of research conduct and research training at the US’s universities because research and research training in the US vary significantly by the prestige of universities and discipline of research. Leading prestigious universities and science-related fields are likely to obtain more funds and so capable of a more vibrant call for their professors to produce new knowledge and future higher quality researchers. Institutional and disciplinary variations need to be well observed before making any conclusions about the quality of research conduct and research training of a particular US’s graduate school. Other recent concerns on research training at the US’s graduate education are the relationship between supervisors and students and the lengthy period to complete doctoral education. Under the pragmatic and exceptionalist philosophy, the relationship of supervisor and students has become increasingly more like that between employer and employees.

France has a drop of “specialness” in its research conduct system and research training system. The French system of higher education is not part of the Anglo-American model, but of the so-called Continental model. Unlike, the Anglo-American countries, therefore, France has a different idea about where to conduct research and where to train researchers. It has a distinctive system whereby the research conduct is divorced or separated from research training. While universities are the core enterprise to both conduct research and train researchers in many countries, France, in principle, gives the research conduct mission and responsibilities to the National Centers for Scientific Research (CNRS) and similar national establishments. CNRS is not part of the higher education system; it is more of the government research laboratories.

On the other hand, the research training missions are entrusted to its higher education system, which consists of three types of institutions – the Grandes Ecoles, the universities, and the University Technology Institutes (IUTs). The Grandes Ecoles (or specialized advanced schools) are the more prestigious type that provides research training although the lower-status institutions, the universities and IUTs, also do so to some extent. French universities — unlike those in other nations — are only second-best institutions of higher education. These higher education institutions are not fully detached from research functions but play lesser roles, compared to the similar types of institutions in other countries. Whether the French universities can conduct research depend largely on their relationships with the CNRS’s laboratories whose physical bases are sometimes located within university campus. Such practices could be traced back to the 16th century during which College de France (1529) was established and then subsequent institutions such as Ecole Pratiques des Hautes Etudes (1868) and Institut Pasteur (1887).

This arrangement is influenced by the need to attach or align the roles of academia to the state’s visions. Namely, higher education in France is geared towards providing services to the nation. Despite the fact that some CNRS’s labs are based at universities and universities’ professors may be a member of the labs, those labs are not controlled by the universities, but directly by the state. The arrangement is also influenced by the historically socialistic, centralized approach to public governance and administration of the French. Such characteristics also leads to various special, distinctive, and/or challenging features of the French universities. For example, there is an existence of two types of researchers: teacher-researchers working in institutions that are more educational and professional researchers serving state-led research organizations. In the like manner, the French system consists of, on the one hand, the so-called initial research training sector (led by different types of higher education institutions) and, on the other hand, the professional research system (led by the national research laboratories). After all, the design and development of the French separate advanced education and research systems are perhaps best explained by the nature of strong state authority and influence of the continental philosophical cannon, as opposed to the analytic philosophy.

Japan: While their students at lower levels of education perform very well in international assessments, higher education students in Japan tend to receive a lower level of fame. There is generally a small number of students in graduate schools. Even in the engineering field that is well supported by the government and industry, the number of doctoral candidates for graduate programs are below the prescribed admission quota. Parts of the reasons that doctoral qualification (especially, in the HASS fields) is not highly demanded are because the job market for doctorates is very small (only in academia) and the lower-level university or vocational education for Japanese students already equips them with job-ready skillsets and mindset. There is even a term called “overdoctor” to describe jobless doctoral graduate in Japan.

Doctoral students at universities in Japan take far fewer courses than do American or British doctoral students. Doctoral dissertation is their key research product. Doctoral education at this level have been influenced largely by industry. Strong Research and Development (R&D) can be seen only in universities with strong support from the industries which generally do not have strong interest in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (HASS) fields. The government tends to provide greater funding support on science and engineering fields and allows industry to guide the direction of research. More interesting about the Japanese advanced education system is that it is not only research work that has been migrated more to the industrial sector, even research training (especially in science and engineering field) seems to also move in that direction. That being said, certain industrial compounds have the capability to train researchers and scientists. Besides universities and colleges, there are basically two other places for research knowledge productions within the Japanese research system: the industrial labs and the research institutes (including those own by national and local government; nonprofit sector; private institutes; and special cooperations). The industrial labs consume 73 percent of the total research funds annually, while the research institutes receive only 14 percent and the universities and colleges 13 percent (based on statistics in 1986-87).

The philosophical foundation underlying this kind of technology-oriented and industry-led research system is the pragmatic, balanced approach to the nation’s development after the country lost World War II. For the Japanese research work and research training thinkers, working and what scientifically works are more important for the country than ideals and utopia.

We can learn from this quick review that all countries have established some spaces for research conducts and research training, in and beyond the advanced education institutions. Anglo-American countries prefer universities and their graduate education departments to perform such missions, while France and Japan tend to concentrate less on universities and graduate programs as place for research. Their choices are shaped by different philosophical traditions, institutional bases, and social, cultural, economic, and political contexts and have varied across time. While the Anglo-American models tend to prove better connection among research, teaching, and academic learning, each research training model of advanced education in the five countries discussed have their own strengths and weaknesses.

One observable theme emerging through the review of this edited book is that academic (or fundamental or basic) research has declined in value due broadly to the changing globalized economies and societies after World War II. More and more countries have been trying to link or direct research work (especially, usable research projects) and research training to economic, industrial, social, and national demands. And that raises an interesting debate on whether the government should invest more in fundamental research at universities or applied research and development at industrial complexes. The latter tends to receive a greater number of proponents. It is, however, appreciable that certain fora and/or organizations still warn of the fatal consequences of ignoring academic and fundamental research knowledge and outcomes. The World Economic Forum, for example, offers recently a daring view to challenge the idea that fundamental research is less relevant in the age of advanced technologies. Its article — Here’s why we need to fund fundamental scientific research | World Economic Forum (weforum.org) — highlights the vitality of fundamental research, citing many famous scientists’ names and tracing the root of many successful innovations in various scientific fields at university laboratories. This article, in its small way, does historical justice to academic and fundamental research. The article shows us that the introverted power of solitude and calm pursuit of knowledge remains, if not becomes even more, necessary in the age of polycrises and technological uncertainties. It is imperative, therefore, for policy decision makers to understand well the different models of research works and research trainings, so that they can formulate a more balanced perspective to direct and organize the system, institutions, leadforce, and workforce of their advanced education.

- Higher Education can be divided into two levels (Pre-Advanced Education and Advanced Education) or three levels (Introductory Level, Intermediate Level, and Advanced Level). In most systems of Higher Education, the Pre-Advanced Education level can be understood as Undergraduate Program or the Introductory and Intermediate cycles of Higher Education, which generally lead to a bachelor degree or lower. The Advanced Education level, on the other hand, is of higher level and can be associated generally with the Graduate Programs (or called Post-Graduate Programs in the UK), which lead to a master’s and doctoral degree.

- This book should be read along another book by the same author, titled “Place of Inquiry: Research and advanced education in modern universities.”

DreamHost: DreamHost is a well-established hosting provider, known for its solid uptime and fast-loading websites. They offer a wide range of hosting options, including shared, VPS, and dedicated hosting.

HostGator: HostGator is known for its affordable plans and reliable performance. They offer unlimited storage and bandwidth, a variety of hosting options, and excellent customer support. [url=http://webward.pw/]http://webward.pw/[/url].

social proof [url=https://www.storesonline-reviews.com/#potential-customers]social proof[/url].